| Book title

| Translator(s), Commentator(s), and Editor(s)

| Parallel text (with original German)

| Comments

|

| The Best of Rilke

| Walter Arndt

| Yes.

| Tries to reproduce the rhyme and meter of the originals.

To achieve the rhyme, Arndt sometimes adds words (such as "wrist" in the sample below)

that are not in the original.

|

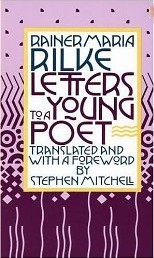

| Duino Elegies

| Stephen Mitchell

| No (in little Shambala edition).

|

|

| New Poems [1907]

| 1984: Edward Snow

| Yes.

| "What specifically is 'new' about the New Poems?

The most striking transformation occurs in Rilke's language,

which grows simultaneously more lucid and complex.

Compression of statement and elimination of authorial self are taken

to their extremes in the pursuit of an objective ideal." [p. x of the Introduction].

The translations tend to conform closely (perhaps too closely) to the German

grammar, and as a result are less poetic in English than they might have been.

|

| Rainer Maria Rilke: Translations from the Poetry

| M.D. Herter Norton

| Yes.

|

|

| The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke

| Stephen Mitchell

(Introduction by Robert Hass)

| Yes.

|

|

| Selected Poems of Rainer Maria Rilke

| 1981: Robert Bly

translates selections from five of Rilke's six major collections;

adds introductory comments.

| Yes.

| The translations are ok but a little prose-like.

Helpful comments, however, including:

"When I first read Rilke, in my twenties, I felt a deep shock upon realizing

the amount of introversion he had achieved, and the adult attention he paid to inner states.

... Rilke knows ... that our day-to-day life, with its patterns and familiar objects,

can become a husk that blocks anything fresh from coming in.

...In the fall, he found, one can look down long avenues of trees inside,

when the vision is not blocked by leaves."

|

| Sonnets to Orpheus

| M.D. Herter Norton

| Yes.

| 32 interesting pages of notes.

Translation sometimes stilted; prefer Mitchell's versions.

|

| Number

| Written from:

| Date:

| Quotation from Stephen Mitchell's translation:

|

| 1

| Paris

| February 17, 1903

| This most of all:

ask yourself in the most silent hour of the night:

must I write?

|

| 2

| Viareggio, near Pisa (Italy)

| April 5, 1903

| Irony: Don't let yourself be controlled by it, especially during

uncreative moments. When you are fully creative, try to use it,

as one more way to take hold of life. Used purely, it too is pure,

and one needn't be ashamed of it; but if you feel yourself becoming

too familiar with it ... then turn to great and serious objects, in

front of which it becomes small and helpless.

... If I were to say who has given me the greatest experience

in the essence of creativity, its depths and eternity, there are

just two names I would mention:

[Jens Peter] Jacobsen, that great, great poet,

and Auguste Rodin, the sculptor, who is without peer among

all artists who are alive today.

|

| 3

| Viareggio, near Pisa (Italy)

| April 23, 1903

| Read as little as possible of literary criticism —

such things are either partisan opinions, which have become

petrified and meaningless, hardened and emptied of life,

or else they are just clever word games, in which one view

wins today, and tomorrow the opposite view.

... Allow your own judgments their own silent, undisturbed development,

which, like all progress, must come from deep within and cannot be forced or hastened.

|

| 4

| Worpswede, near Bremen

| July 16, 1903

| Have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and try to love

the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books

written in a foreign language.

Don't search for the answers, which could not be given to you now,

because you would not be able to live them.

Live the questions now.

Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually,

without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.

... Sex is difficult; yes. But those tasks that have been entrusted

to us are difficult; almost everything serious is difficult;

and everything is serious.

|

| 5

| Rome

| October 29, 1903

| Rome ... makes one feel stifled with sadness for the first few days:

through the gloomy and lifeless museum atmosphere that it exhales,

though the abundance of its pasts

... through the terrible overvaluing, sustained by scholars and philologists

and imitated by the ordinary tourist in Italy,

of all these disfigured and decaying Things, which, after all,

are nothing more than accidental remains from another time

and from a life that is not and should not be ours.

... But there is much beauty here, because everywhere there is much beauty.

|

| 6

| Rome

| December 23, 1903

| I know your profession is hard and full of things that contradict you,

and I foresaw your lament and knew that it would come.

Now that it has come, there is nothing can say to reassure you, I can

only suggest that perhaps all professions are like that, filled with demands,

filled with hostility toward the individual, saturated as it were with the

hatred of those who find themselves mute and sullen in an insipid duty.

|

| 7

| Rome

| May 14, 1904

| It is also good to love: because love is difficult.

For one human being to love another human being: that is perhaps the most difficult

task that has been entrusted to us, the ultimate task, the final test and proof,

the work for which all other work is merely preparation.

That is why young people, who are beginners in everything, are not yet

capable of love: it is something they must learn.

... this more human love

... the love that consists of this:

that two solitudes protect and border and greet each other.

|

| 8

| Borgeby gârd, Flädie, Sweden

| August 12, 1904

| Why do you want to shut out of your life any uneasiness, any misery,

any depression, since after all you don't know what working these conditions are

doing inside you?

Why do you want to persecute yourself with the question of where all this is coming from

and where it is going?

Since you know, after all, that you are in the midst of transitions and you wished for

nothing so much as change.

... you must be patient like someone who is sick,

and confident like someone who is recovering, for you are both.

Don't observe yourself too closely.

Don't be too quick to draw conclusions from what happens to you; simply let it happen.

Otherwise it will be too easy for you to look with blame (that is: morally)

at your past, which naturally has a share in everything that now meets you.

... One must be so careful with names anyway; it is so often the name

of an offense that a life shatters upon, not the nameless and personal action itself,

which was perhaps a quite definite necessity of that life and could have been absorbed by it without

any trouble.

|

| 9

| Furuborg, Jonsered, in Sweden

| November 4, 1904

|

Your doubt can become a good quality if you train it.

It must become knowing, it must become criticism.

Ask it, whenever it wants to spoil something for you,

why something is ugly, demand proofs from it,

and you will find it perhaps bewildered and embarrassed, perhaps also protesting.

... and the day will come when, instead of being a destroyer, it will become one of

your best workers — perhaps the most intelligent of all the ones that

are building your life.

|

| 10

| Paris

| the day after Christmas, 1908

| Art too is just a way of living, and however one lives, on can,

without knowing, prepare for it; in everything real one is closer to it,

more its neighbor, than in the unreal half-artistic professions, which,

while they pretend to be close to art, in practice deny and attack the

existence of all art —

as, for example, all of journalism does and almost all criticism and three quarters

of what is called (and wants to be called) literature.

I am glad, in a word, that you have overcome the danger of landing in one of those

professions, and are solitary and courageous, somewhere in a rugged reality.

|

Highlights of Poetry.

Highlights of Poetry.

Index of poetry.

Index of poetry.

How to Write Poetry.

How to Write Poetry.

Books read.

Books read.

Haibun.

Haibun.

Haiku.

Haiku.

Hay(na)ku.

Hay(na)ku.

Rengay.

Rengay.

Tanka.

Tanka.

Concrete.

Concrete.

Ghazal.

Ghazal.

Lai.

Lai.

Pantoum.

Pantoum.

Prose poem.

Prose poem.

Rondeau.

Rondeau.

Rubáiyát.

Rubáiyát.

Sestina.

Sestina.

Skaldic verse.

Skaldic verse.

Sonnet.

Sonnet.

Terza rima.

Terza rima.

Triolet.

Triolet.

Tritina.

Tritina.

Villanelle.

Villanelle.

Adam Zagajewski.

Adam Zagajewski.

Aleda Shirley.

Aleda Shirley.

Anne Carson.

Anne Carson.

The Beowulf Poet.

The Beowulf Poet.

Billy Collins.

Billy Collins.

Billy Collins exercise.

Billy Collins exercise.

Snorri's Edda.

Snorri's Edda.

Carl Dennis.

Carl Dennis.

Charles Atkinson.

Charles Atkinson.

Chase Twichell.

Chase Twichell.

Corey Marks.

Corey Marks.

François Villon

François Villon

Franz Wright.

Franz Wright.

Galway Kinnell.

Galway Kinnell.

Gary Young.

Gary Young.

The Gawain Poet.

The Gawain Poet.

Jack Gilbert.

Jack Gilbert.

Jane Hirshfield.

Jane Hirshfield.

Jean Vengua.

Jean Vengua.

J. Zimmerman.

J. Zimmerman.

J. Zimmerman (haiku).

J. Zimmerman (haiku).

J. Zimmerman (tanka).

J. Zimmerman (tanka).

Jorie Graham.

Jorie Graham.

Karen Braucher.

Karen Braucher.

Karl Shapiro.

Karl Shapiro.

Kay Ryan.

Kay Ryan.

Britain;

Britain;

USA.

USA.

Len Anderson.

Len Anderson.

Les Murray.

Les Murray.

Li-Young Lee.

Li-Young Lee.

Linda Pastan.

Linda Pastan.

Louise Glück.

Louise Glück.

Nordic Skalds.

Nordic Skalds.

Pulitzer Poetry Prize (U.S.A).

Pulitzer Poetry Prize (U.S.A).

Rainer Maria Rilke.

Rainer Maria Rilke.

Richard Hugo.

Richard Hugo.

Robert Bly.

Robert Bly.

Sara Teasdale.

Sara Teasdale.

Shiki (haiku).

Shiki (haiku).

Snorri's Edda.

Snorri's Edda.

Stephen Dunn.

Stephen Dunn.

Ted Kooser.

Ted Kooser.

W.S. Merwin.

W.S. Merwin.